WTF Venus?

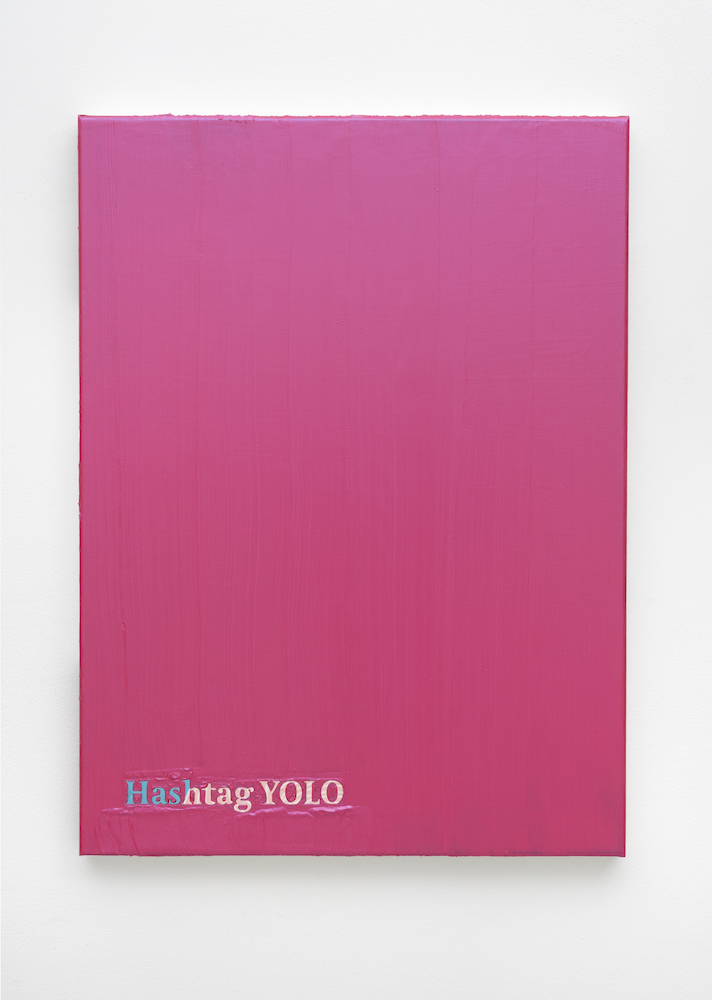

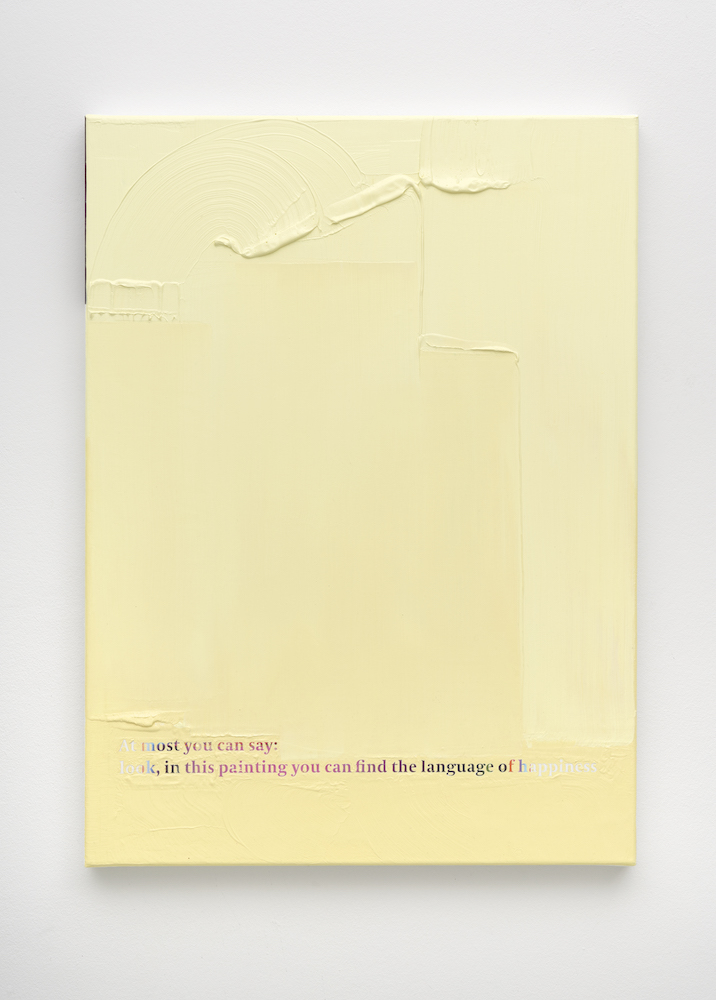

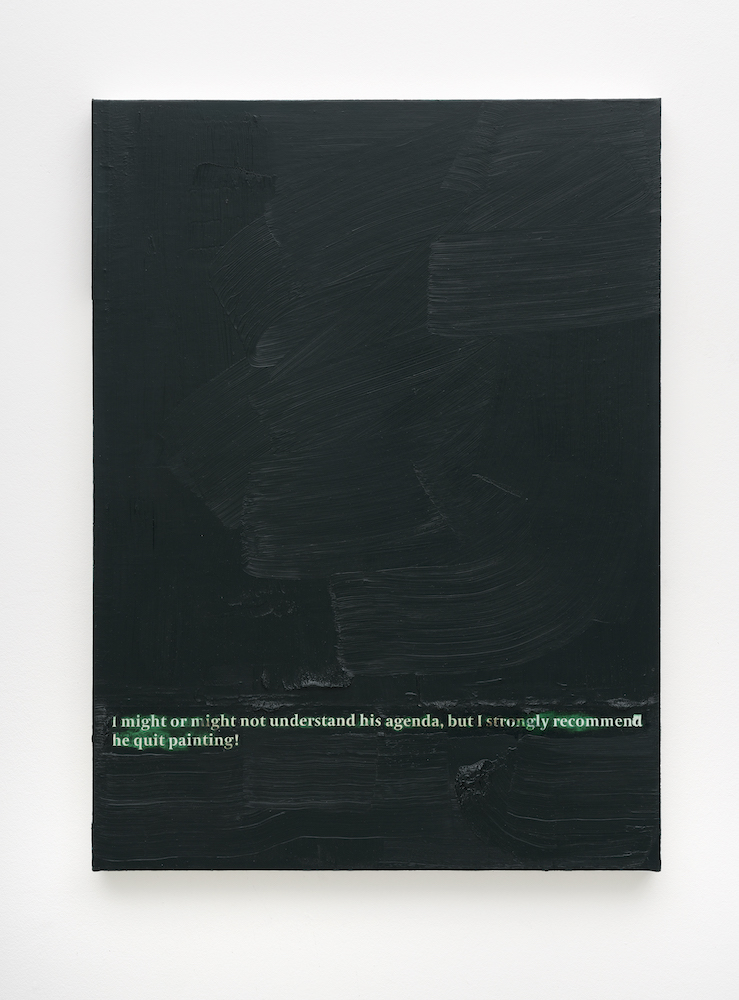

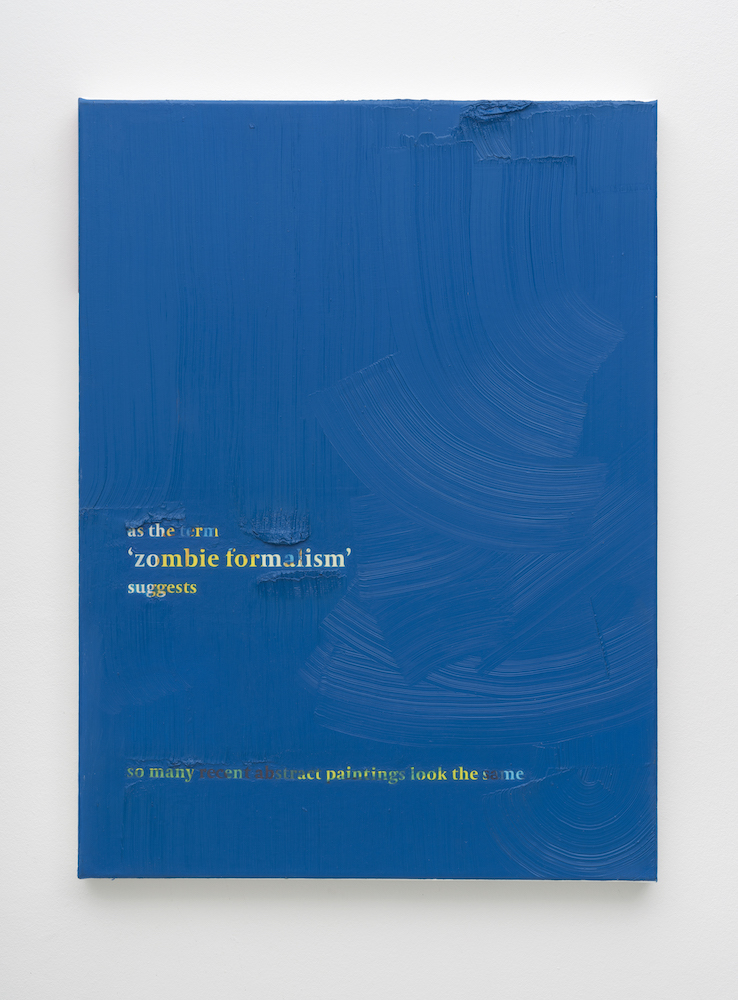

Artworks

80 x 110 cm

80 x 110 cm

ca. 140 x 30 cm

Information

Please scroll down for English Version.

Schon mal einen Muffin gekauft und sich gedacht: Wäre es nicht toll, einfach nur das Muffinförmchen aus Papier kaufen zu können? Solche Überlegungen stellt man wohl nur an, wenn man findet, das Förmchen sei das Beste am ganzen Muffin. Dieser Wunsch jedenfalls und die Sehnsucht nach einem Ideal bilden den Herzschlag zu Murray Gaylards Ausstellung mit dem Titel „WTF Venus?“. Der Geistesblitz, auf dem diese Ausstellung beruht, kam ihm nachdem er im Atelier einen Muffin gegessen hatte: er betrachtete die Papierform, diese leere Hülle an der noch Teigreste klebten, und sinnierte über Herzensangelegenheiten und die Liebe nach. In diesem Moment erschien ihm die Form des Papierobjekts Anklänge an die Geburt der Venus (c. 1480) des italienischen Malers Sandro Botticelli zu haben.

Zwei Skulpturen, die für Ausstellung namensgebend sind, ragen senkrecht in die Höhe und tragen als Abschluss am oberen Ende jeweils eine benutzte Muffinform (je von einem Muffin mit unterschiedlichem Geschmack) die in Kunstharz getunkt wurde. Sie verkörpern die Genese des Konzepts und geben den Ton der Ausstellung vor: es geht um Intimität, Liebe, Sehnsüchte, Verlangen, Ideale. Stahlrohre bilden die Sockel für die Muffinformen, die uns nicht nur in die goldene Ära Italienischer Malerei versetzen, sondern hier auch als eine Geste der Liebeswerbung stehen, erinnern sie doch an Pfauenhähne, die mit ihren Federn ein Rad schlagen. Gaylard verewigt hier eine Abwesenheit, den Geist des Muffins, aber gleichzeitig erregt er auch unseren Appetit, erzeugt ein Gelüst. Im Gegensatz zu Botticellis Muschelschale sind die Papierformen "geschlossen" – und bilden so eine Metapher für eine unerreichbare Venus, eine unzugängliche Intimität, oder eine Liebe die sich nicht entfalten kann.

Die Skulptur "I said don’t touch me" führt diesen Gedankengang weiter, symbolisiert aber eine andere Art der unerfüllbaren Sehnsucht und behandelt die Körperlichkeit von Intimität. Sie besteht aus einem langen, bemalten Stock, der immer wieder in Kunstharz getaucht wurde, woraufhin das vom Stock herabtropfende Material natürlich aussehende (Eis-)zapfen formte. Im Gegensatz zu einem Kaktus sind diese Zapfen fragil und schutzlos, durch Berührung könnten sie brechen. Das Werk spielt somit auch mit dem vorherrschenden Status Quo in Galerie und Museumsräumen, der allgegenwärtigen Regel, die unseren Umgang mit Kunstwerken beherrscht: Anfassen verboten! Die Schönheit eines Kunstwerks kann bisweilen so verführerisch wirken, dass wir es mit allen Sinnen erfahren wollen. Wir sind neugierig, wie sich diese Schönheit anfühlen würde: aber wir bleiben eingeschränkt, man könnte sogar sagen gehemmt, in unserem Verlangen.

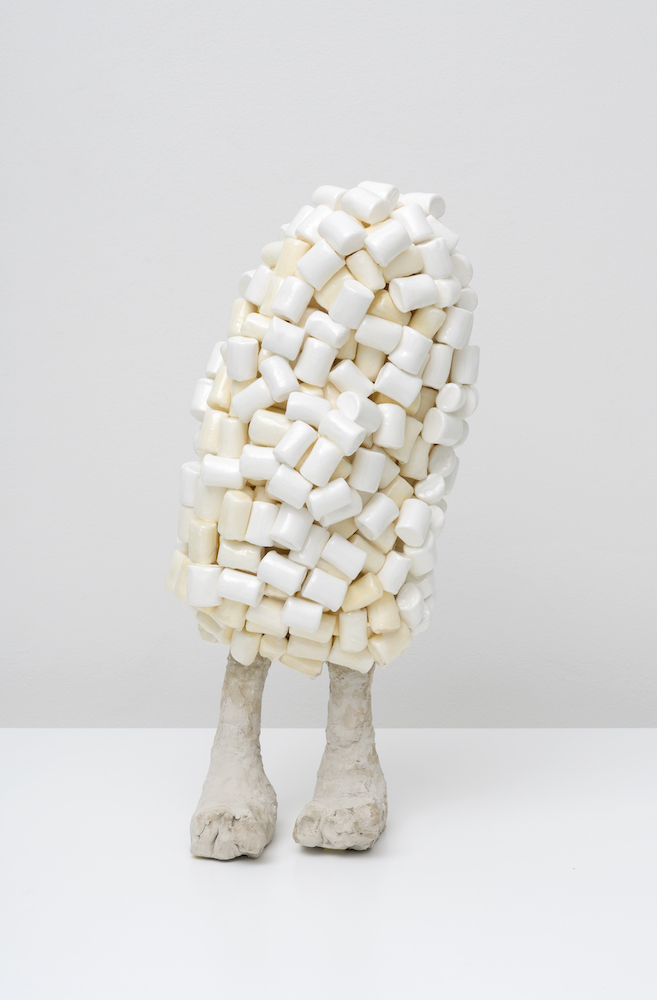

Die Arbeit "Single White Male" dreht sich ebenfalls um Versuchung. Sie besteht aus einem Objekt aus ungebranntem Ton, das über und über mit Marshmallows bedeckt ist, die ebenfalls in Kunstharz getaucht wurden; nur die Füße der Skulptur schauen heraus. Der Künstler fragte sich: Was könnte verlockender sein als jemand der von Marshmallows übersät ist? Gleichzeitig verweist die Skulptur auf ein Ideal, das im echten Leben nicht existiert, und auf das Verlangen und die Frustration, die der Suche nach einem alleinstehenden Mann innewohnen.

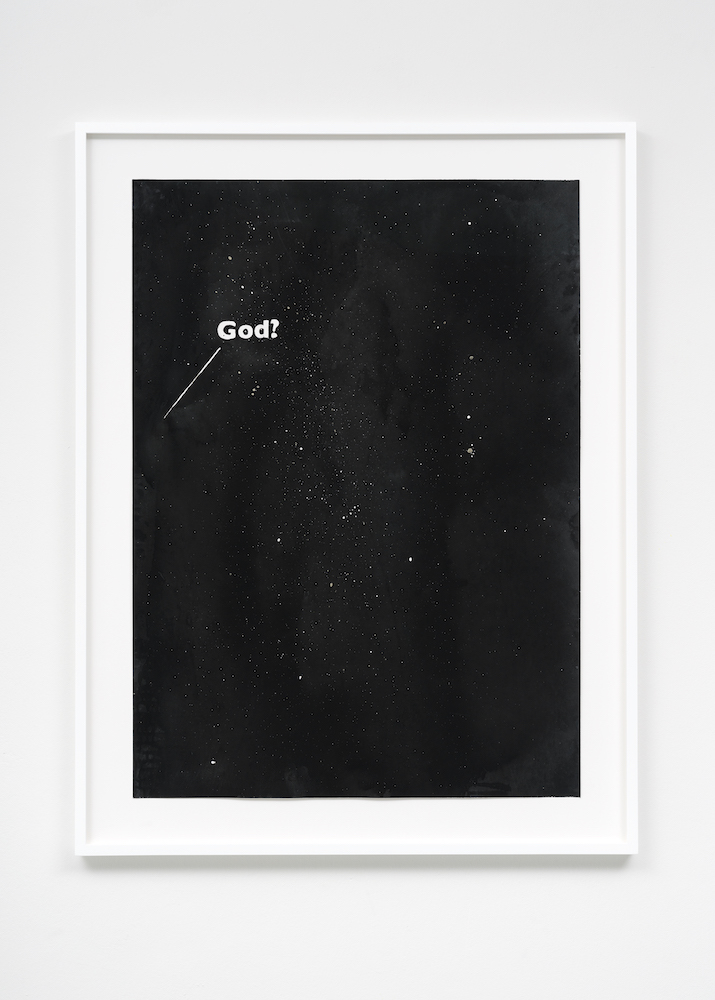

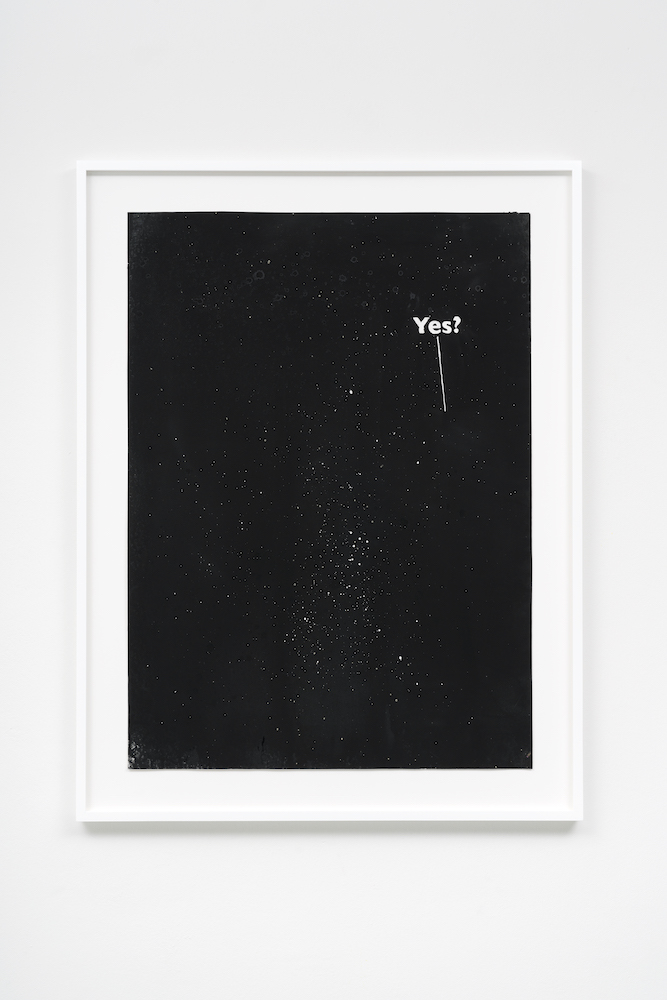

Die Skulpturen sind im Grunde genommen paradoxe Metaphern für Begierde, Verführung und der Furcht vor Intimität, der Angst, einander nahe zu kommen, und der Sehnsucht nach Berührung durch eine andere Person. Heutzutage verweist Berührung auch auf Touchscreens, Mobiltelefone und unseren enormen Grad der Vernetzung, ebenso wie auf unsere Übersättigung durch Dating Apps, die für den Zweck entwickelt wurden, uns einander näher zu bringen. Gaylard geht der Frage nach, wie wir uns in einer derart hyper-vernetzten Welt so abgekoppelt fühlen können. Dieses Gefühl der Isolation weicht der Frage nach unserer Rolle im Leben und einer Empfindung, die dem Schweben, dem Losgelassen-sein ähnelt. Ein Aquarell des Universums, der Sterne, scheint gleichzeitig einen Abgrund darzustellen. Das Gemälde ist in ein Gespräch mit sich selbst verwickelt. Die Frage „God?“ auf der linken Seite wird von rechts beantwortet: „Yes?“. Ein Anflug von Humor, aber auch das Gefühl, dass es da Hoffnung gibt.

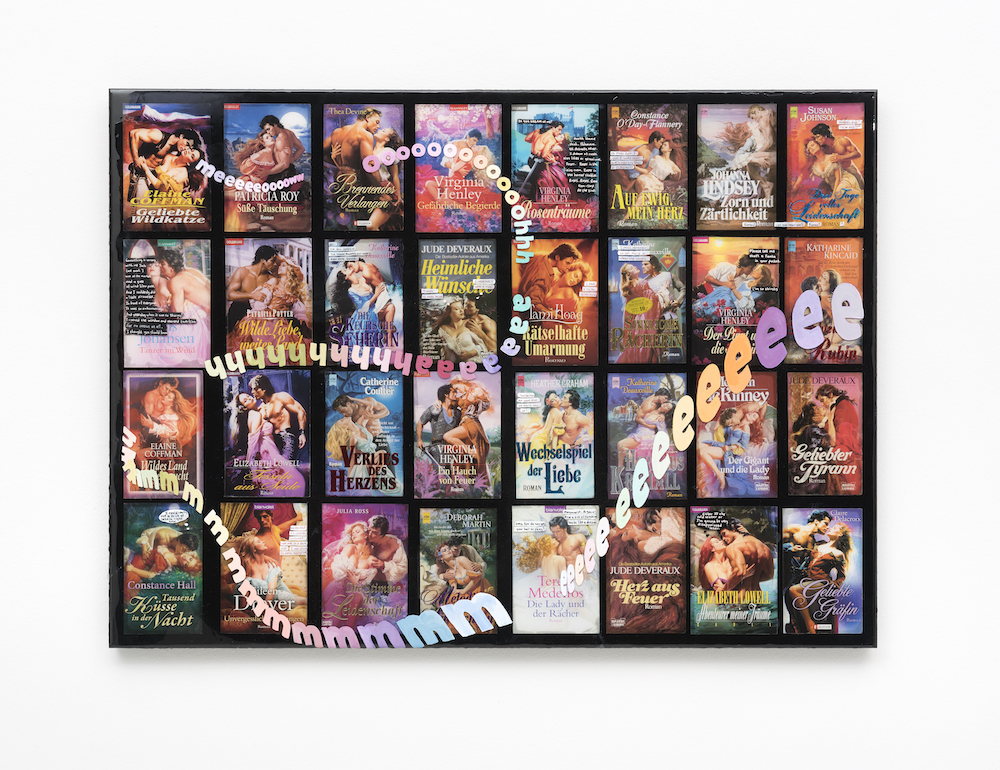

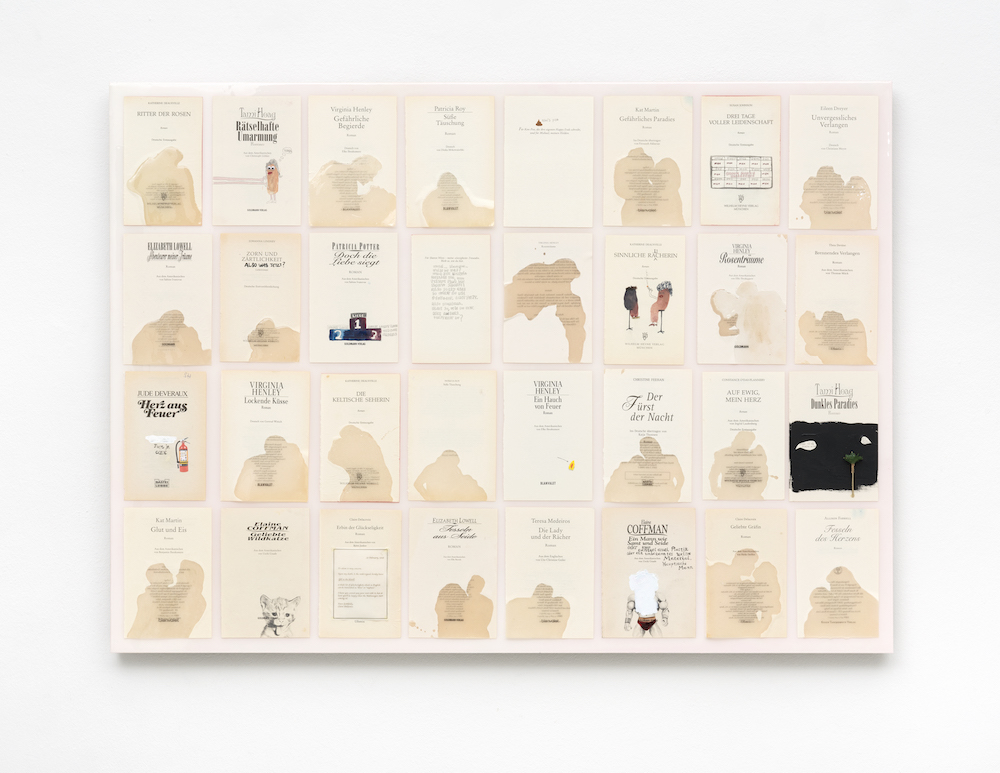

Eine der eher autobiografischen Arbeiten in der Ausstellung dreht sich um persönliche Erinnerungen an die Mutter des Künstlers, eine begeisterte Leserin von Liebesromanen. Die Arbeit besteht aus drei großen Tafeln, auf die Gaylard abgerissene Buchdeckel von Liebesromanen geklebt hat, wodurch ein Raster von Bildern entsteht: sie zeigen schmachtende Frauen, Umarmungen, verbotene Küsse, halbausgezogene Kleider drapiert über lechzende Körper, und imposante Männer mit ziselierten Bodies, die Frauenkörper mit starkem Griff an sich ziehen. Die Tafeln sind des Weiteren mit Text überzogen – stöhnende „oooohs“ und „aaahs“ –wobei die Werkgruppe den überaus passenden Titel "the moans and groans of a frustrated house wife" trägt. Eine weitere Tafel präsentiert Titelseiten von Novellen, auf die der Künstler mit Kunstharz die Formen der Körper wie sie auf den Originalcovern erscheinen gemalt hat. Selbst in den „Schatten“ dieser sich intim umschlingenden Figuren erkennen wir dank der verwendeten Geschlechterstereotypisierung sofort, welche männlich und welche weiblich konnotiert sind. Jedes Titelblatt ist außerdem mit einer humorvollen, nicht ganz ernst gemeinten Neuinterpretation des jeweiligen Titels versehen: Gaylard paart so beispielsweise den Titel „heart of fire“ mit einem Feuerlöscher und dem Vermerk „just in case“.

Die Eigenheit seiner Mutter beeinflusste ihn. Basierend auf ihrer Lektüre malte er sich die Vorstellung eines perfekten Mannes aus, vielleicht sehnte auch er sich nach dem unerreichbaren Ideal des perfekten Mannes oder Partners. Mit der Zeit fand der Künstler heraus, dass Studien nach die Zielgruppe für dieses Literaturgenre Frauen sind, die in ihren Ehen unglücklich und unerfüllt sind. Als Madame Bovary macht sich das Werk über das Genre des Liebesromans lustig, beschreibt aber gleichzeitig auch die Sehnsucht nach einer unerreichbar bleibenden Liebe und ein unrealistisches Verständnis von Romantik und Erotik, das tatsächlich auf einem Hilfeschrei basiert. Vielleicht ist diese Werkserie auch kathartischer Natur und erlaubt dem Künstler, nicht nur seine Sicht seiner Mutter, Familie und Kindheit aufzuarbeiten, sondern auch Intimität an sich besser zu verstehen.

Die Arbeiten in der Ausstellung basieren auf persönlichen Gefühlen, Erinnerungen und Angelegenheiten die für die Selbstreflexion des Künstlers zentral sind: „Auf eine bestimmte Art ist die Ausstellung autobiografisch. Es ist fast so, als würde sie die verschiedenen Stadien aufzeigen, die man durchläuft, wenn man sein Verständnis von Intimität aufarbeitet und dies jemand anderem kommunizieren kann. Einsamkeit und das künstliche Gefühl von Verbindung“ wie Gaylard es beschreibt. Die Arbeiten in der Ausstellung sind durchzogen von einem Gefühl der Isolation, Andeutungen einer haltlosen Welt und der Sehnsucht, dazuzugehören. Gaylards künstlerische Arbeit ist allegorisch, oszilliert zwischen Objekten, Gefühlen, der Welt der Natur, dem digitalen Raum, der Körperlichkeit unserer Emotionen ebenso wie der Symbolik und dem bildlichen Ausdruck durch welche letztere sich gestalten. Seine Skulpturen sind visuelle Haikus über das Menschsein.

Amira Gad

Ausstellungskuratorin, Serpentine Galleries

Have you ever had a muffin and thought: Wouldn’t be great if you could buy only the paper muffin form? That’s if you agree that muffin forms are the best part. This desire and the longing for an ideal are the heartbeat of Murray Gaylard’s exhibition titled ‘WTF Venus?’ The epiphany for this show came to him when he was eating a muffin in his studio, the remainders of the eaten muffin still clinging to its paper form, its shell, which lay on the desk of his studio as he pondered matters of the heart and love. At this moment the shape of the paper appeared to him to be reminiscent of Italian painter Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (c. 1480), its folds recalling the shell from which Venus emerges in the masterpiece.

Two sculptures which lend the exhibition its title stand tall, with used muffin forms (each from a different flavour muffin) that have been dipped in resin at their tops. They represent the birth of the concept and set the tone of the show: intimacy, love, desires, longing, ideals are at stake here. Steel pipes form the pedestals for the muffin forms, which not only plunge us into the golden era of Italian painting but, like a peacock opening up its feathers, also act as a gesture of courtship. Gaylard immortalises an absence, the ghost of the muffin, and rouses our appetite, creates a craving. Unlike Botticelli’s shell, the paper is ‘closed’ – a metaphor for an unattainable Venus, an intimacy that is shut-off or a love that cannot be birthed.

The sculpture I said don’t touch me continues along this thread. It symbolises another form of unattainable desire and revolves around the physicality of intimacy. The piece consists of a long, painted stick that has been dipped in resin numerous times, allowing the resin to drip off and naturally form icicles. Unlike a cactus, the icicles are fragile and vulnerable, they may break when touched. The work also points to the status quo of how we are meant to behave around artworks presented in gallery spaces: we’re not allowed to touch. While the beauty of an artwork can be so appealing that we want to engage with it with all our senses and our sense of curiosity wants us to feel the beauty, we remain restricted – perhaps even repressed.

Temptation is also present in the work Single White Male, where an object made of unfired clay has been completely covered in marshmallows dipped in resin, with only the feet of the sculpture revealed. As the artist said to himself: What could be more tempting than someone covered in marshmallows? At the same time, the piece also points to an illusory ideal and to the feelings of desire and frustration related to the search for the rare single man.

The sculptures are essentially a paradoxical metaphor for desire, temptation and a fear of intimacy, a fear of getting close to each other, or the longing of another person’s touch. Today, touch also points to our touching our phones, and in turn also to our over-connectivity through our touch smartphones and the saturation with dating applications meant to help bring us closer to each other. Gaylard asks: ‘How can we feel so disconnected in such a hyper-connected world?’ From this feeling of disconnect, a sense of floating comes about through the questioning of the role that we play in this world. A watercolour of the universe, of the stars appears to be a watercolour of an abyss. The painting is in conversation with itself. The question ‘God?’ appears on the left and the right side of the painting answers ‘Yes?’ A touch of humour but also a sense of hope.

One of the more autobiographical works in the show consists of three large boards and is based on personal memories of the artist’s mother, who was an avid reader of romance novels. Gaylard takes the covers of romance novels, rips them off and glues them onto board, resulting in a grid composed of lusting women, embraces, forbidden kisses, dresses draped over half-naked bodies, and fit strong men with an imposing grip. The board is overlaid with text, moaning ‘oooohs’ and ‘aaahs’, with this body of work aptly titled ‘the moans and groans of a frustrated house wife’. Another board presents the title pages of the novels onto which Gaylard has painted the stencil form of the original cover in resin. Even the ‘shadows’ of the figures in an intimate embrace taken from a cover allow us to recognise the man and the woman by virtue of gender stereotyping. A humorous re-interpretation of the title has been added to each title page, such as the tongue-in-cheek coupling of the title “heart on fire” with a fire extinguisher and the remark ‘just in case’.

This memory of his mother was to have an impact on the artist as he began to paint the image of the perfect man based on the covers of these novels – while perhaps also longing for the unachievable ideal of that perfect male or partner. He would also come to understand that, as studies have shown, the target audience for this genre of literature is women who are unhappy and unsatisfied with their marriages. As a Madame Bovary, the work pokes fun at the genre of romance novels and encompasses a craving for a love that is unattainable, as well as referring to an unrealistic idea of romance and eroticism whereby the underlying tone is truly a cry for help. There may be a cathartic nature to this body of work that allows the artist to not only come to terms with a better understanding of his mother, his family, and his childhood, but also of intimacy.

The works in the show take their cues from personal feelings, memories and matters at the core of the artist’s self-reflection: ‘The exhibition is in a way autobiographical, almost delineating the various stages that one can go through in coming to terms with an understanding of one’s own intimacy and in being able to communicate this to another. Loneliness and the fake idea of connectivity’ to quote the artist. The works in the show are riddled with a sense of isolation, the feeling of an abandoned world and a yearning to belong. Gaylard’s practice is parabolic; it oscillates between objects, feelings, the natural world, the digital realm, the physicality of our emotions, and the symbolisms and metaphors through which they take shape. His sculptures are visual haikus that reflect on the human condition.

Amira Gad

Exhibitions Curator, Serpentine Galleries