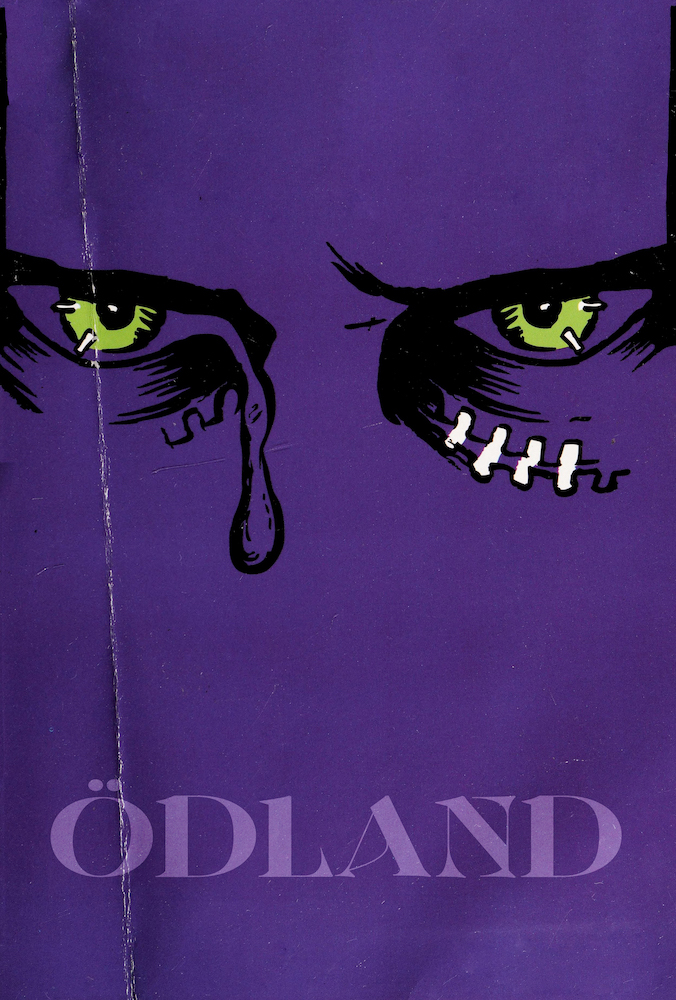

Ödland

Artworks

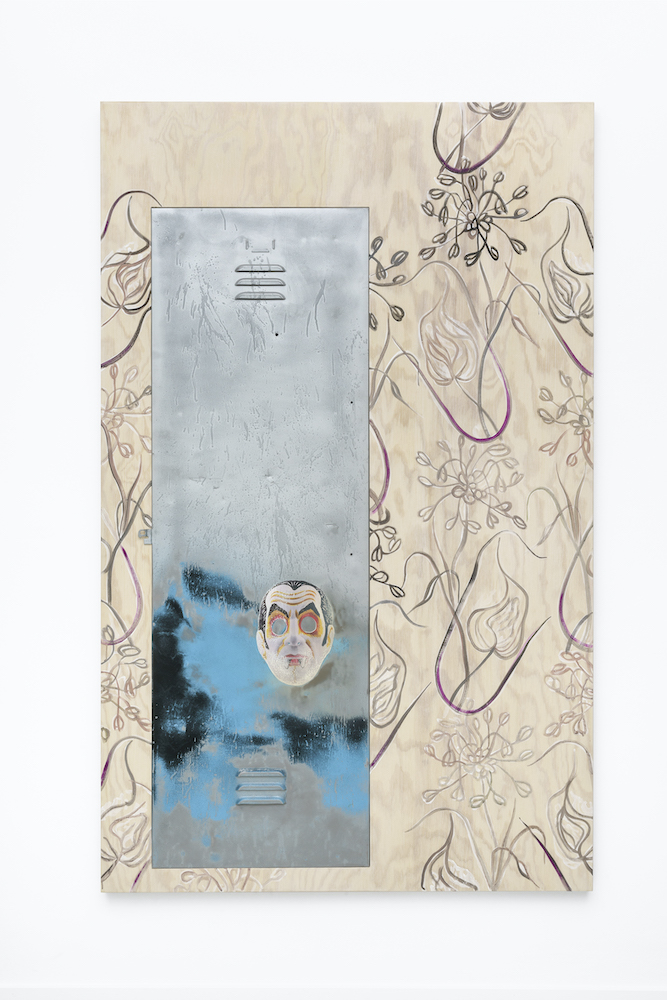

Gesso, Acryl, Gouache auf Holz, Metall, Digitalprint, Lack

200 x 125 x 4,8 cm

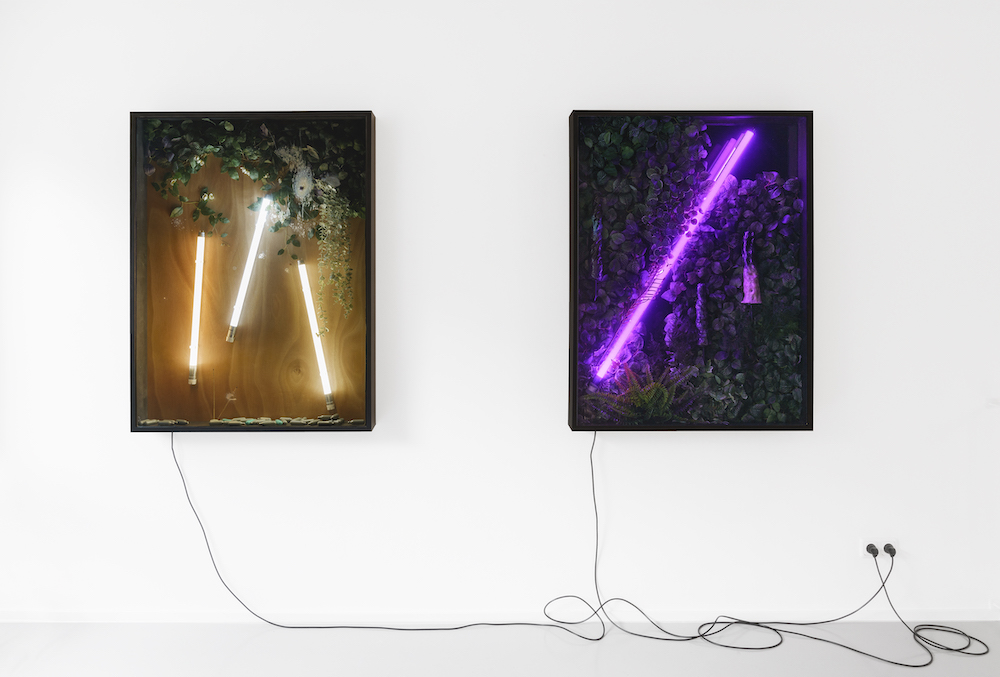

Gesso, Acryl, Öl, Aquarell auf Holz, Metall, Digitalprint, Lack

200 x 125 x 4,8 cm

Gesso, Acryl, Öl, Aquarell auf Holz, Metall, Digitalprint, Lack

200 x 125 x 4,8 cm

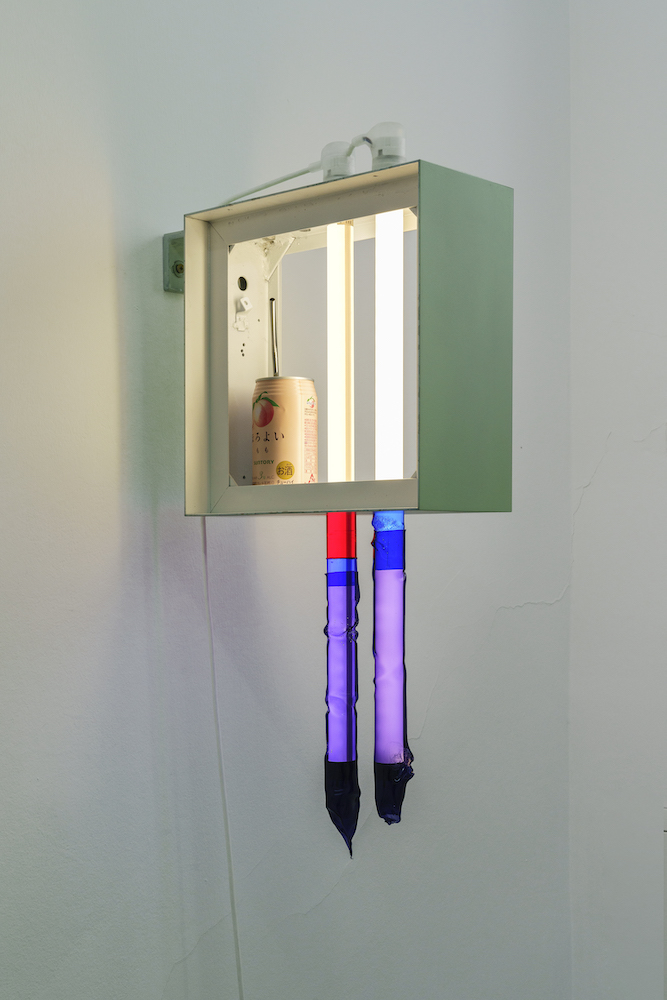

MDF, Glas, Aluminium Dibond, Kunststoff, LED Tubes,

Sodakapseln, Räucherstäbchen, Keramik

123 x 93 x 14 cm

Information

please scroll down for English version.

...a fragment of the past strikes our senses, but it also revives in the imagination all our former life and all the “associated” images with which it is connected. This “memorative sign” is related to a partial presence which causes one to experience, with pleasure and pain, the impossibility of complete restoration of this universe which emerges fleetingly from oblivion. Roused by the “memorative sign”, the conscience comes to be haunted by an image of the past which is at once definite and unattainable. The image of childhood appears ...only to slip away, leaving us prey… (Jean Starobinski, 1966)

Zur Genealogie der Moral (1887) gehört zu Friederich Nietzsches einflussreichsten philosophischen Schriften. Anders als in der klassischen Moralphilosophie versuchte Nietzsche mit diesem Werk Moral nicht zu begründen, sondern vielmehr soziologische, historische und psychologische Entwicklungen als komplexes Beziehungsgefüge für bestimmte moralische Wertvorstellungen nachvollziehbar zu machen. Statt der Frage nachzugehen, wie Menschen handeln, geht es in der Genealogie der Moral vermehrt darum zu verstehen, warum Menschen (Individuen oder Kollektive) glauben, dass sie – oder andere Menschen – auf eine bestimmte Weise handeln sollten. Die auf die Genealogie folgende Ideengeschichte legte es darauf an, die Ursprungssuche hinter sich zu lassen und vielmehr die breite Wirkmacht einer als gemeinhin selbstverständlich wahrgenommenen Ideologie zu verstehen. Vorstellungen linearer Entwicklungen und tatsächlicher Wahrheiten wichen Rekonstruktionen von Um- und Irrwegen, von parallelen philosophischen und historischen Narrativen und Machtverhältnissen.

Anknüpfend an dieses rhizomartige Genealogie-Verständnis, möchte ich Felix Kultaus Schaffen zwischen 2017 und 2021 darstellen und im Folgenden unter der Folie der „Genealogie der Nostalgie“ anschauen. Moral als historisch gewachsen zu begreifen, impliziert sogleich, dass sie sich genauso auch anders hätte konstituieren können, hätten Machtverhältnisse anders gelegen. Wenn folglich nicht mehr von einer Unanfechtbarkeit und Objektivität ausgegangen werden kann, scheint ein Nachdenken – wie ich es Kultau hier unterstellen möchte – über jene Mittel, mit denen sich gewisse Wertvorstellungen durchsetzen haben lassen, umso interessanter. In einer von Akzelerationismus, Fortschrittslogik und (Selbst-)Optimierungswillen überforderten Gegenwart zeigt sich insbesondere das Erwecken einer retrospektiven Sehnsucht als eine wirkmächtige politische Strategie. Die Nostalgie der Vergangenheit ist glückselig und froh, eine „Sehnsucht nach [ . . . ] der Zeit unserer Kindheit, den langsameren Rhythmen unserer Träume“ (Boym 2001, S. XV). Als politisches, kommerzielles, soziales und psychologisches Instrument wird sie eingesetzt, um menschliches Verhalten zu beeinflussen, zu kontrollieren oder zu verändern. Einige der drängendsten Probleme der Gegenwart (ökologische Krise, Migration und Integration, fragmentierte Weltanschauungen, soziale Medien, Fake News, extremistische Politik und Terrorismus) lassen sich durch Wechselwirkungen mit individuellen und kollektiven Kräften der Nostalgie besser verstehen.

Die Macht der Nostalgie liegt in erster Linie darin, ein bestimmendes, einflussreiches menschliches Gefühl zu sein. Für Svetlana Boym, einer der meistzitierten und einflussreichsten NostalgiekritikerInnen, ist Nostalgie „die Sehnsucht nach einer Heimat, die es nicht mehr gibt oder die es nie gegeben hat“; sie ist „ein Gefühl des Verlusts und der Verdrängung, aber auch eine Erinnerung an die eigene Phantasie“; sie ist eine Gegenüberstellung von „zwei Bildern - von Heimat und Fremde, Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, Traum und Alltag“. Die Nostalgie entsteht als Zusammenspiel eines idealisierten Bildes in der Vorstellungskraft des Einzelnen und/oder der Gemeinschaft mit „materiellen“ topografischen Merkmalen (wie Wahrzeichen oder Gebäuden), Gegenständen und sogar Namen. Bestimmte Auslöser, die von Starobinski als „memorative signs“ [Erinnerungszeichen] beschrieben werden, lassen einen ganzen Komplex von vergangenen oder idealisierten Bildern und Erfahrungen aufleben, welche unterschiedliche Ort- und Zeitzonen verschmelzen. Durch das „Erinnerungszeichen“ wird das Bewusstsein von einem Bild der Vergangenheit heimgesucht, wahr oder fiktiv, das nun endgültig und unauslöschlich ist.

Ich möchte dafür argumentieren, Kultaus Skulpturen als materielle wie auch emotionale Collagen eben dieser Erinnerungszeichen zu begreifen: in Form von Stickern, aufgetürmt zu Obelisken, gekratzt in Displayflächen. So bedienen seine Skulpturen sich nicht nur einem Material- und Zeichenfundus, sondern ebenso der mit ihnen verknüpften Erfahrungs- und Erinnerungswerte. Als Kind der Generation Y – post MTV-Generation – referiert Kultau eine Form von Nostalgie, die im Zeichen popkultureller Einflüsse zu lesen ist. Genauer gesagt, ist es vor allem die amerikanische Popkultur, die Mitte/Ende der 1990er über unsere Bildschirme zu flackern begann und sich in unser Konsumverhalten schlich. Zur Hochkultur der Globalisierung stilisiert, versprach sie in einem apolitischen Moment so etwas wie einen universellen Identifikationswert. Was damals zum Inbegriff von individueller Freiheit und Demokratie wurde, existiert heute – wie die Heimat die es niemals gab – vor allem als Erinnerung, als Pop Nostalgie. Ganz im Sinne des neuen Geistes des Kapitalismus finden die gescheiterten Versprechen der globalen Entertainment Industry ihren Weg zurück in die Prozesse kapitalistischer Akkumulation. Wenn die abgetragene Jeans jemals ein Zeichen individueller Unangepasstheit war und die eigenen Erlebnisse attestierte, eifert die Stone-Washed-Jeans heute nicht mehr als einem Trendbewusstsein nach, welches schon lange jede Individualität hinter sich gelassen hat. Konfrontiert mit Kultaus Skulpturen, begegnet einem eine ähnliche Patina. Eine Patina an Freiheitsversprechen, Revolutionsgesten und Partikularismus. Indem er verschiedenste Erinnerungszeichen jener Pop Nostalgie zusammenführt, setzen seine Skulpturen genau dort an, wo Nostalgie nicht nur zur Epidemie einer sich selbst überholenden Gesellschaft geworden ist, sondern als kommodifizierte Form zum Mittel der Manipulation. Immer wieder spielen seine Arbeiten mit ihrem Bewusstsein über die eigene Objekthaftigkeit und den damit verbundenen Warenfetisch (als Lampe, Tür, Display o.ä.), nur um sich dann doch in die eigene Zeichenhaftigkeit und nostalgische Funktionslosigkeit zurückzuziehen. Und obwohl einem durchaus bewusst ist, dass es die amerikanische Popkultur – sprich der reine Kapitalismus – ist, der zu einem spricht, gelingt es Kultau, ein Gefühl von Sehnsucht in einem hervorzurufen, welches nicht nur eine consumer nostalgia rekonstruiert, sondern als komplexes Gefühl die genealogische Verzahnung von Sehnsüchten, Erinnerungen und Wertvorstellungen erahnen lässt: individuell, kollektiv, wahr und fiktiv.

Hendrike Nagel

Literaturverzeichnis

1. Jean Starobinski, The idea of nostalgia, Diogenes 54, 1966

2. Svetlana Boym, The future of nostalgia, Basic Books, 2001

...a fragment of the past strikes our senses, but it also revives in the imagination all our former life and all the “associated” images with which it is connected. This “memorative sign” is related to a partial presence which causes one to experience, with pleasure and pain, the impossibility of complete restoration of this universe which emerges fleetingly from oblivion. Roused by the “memorative sign”, the conscience comes to be haunted by an image of the past which is at once definite and unattainable. The image of childhood appears ...only to slip away, leaving us prey… (Jean Starobinski, 1966)

On the Genealogy of Morality (1887) is one of Friedrich Nietzsche’s most influential philosophical texts. In contrast to classical moral philosophy, rather than attempting to justify morality, Nietzsche here made sociological, historical, and psychological developments comprehensible as a complex set of relationships for certain moral values. Instead of pursuing the question of how people act, the genealogy of morality is more concerned with understanding why people (individuals or collectives) believe that they – or others – should act in a certain way. The history of ideas that followed the Genealogy was concerned with abandoning the search for origins and, much more, with understanding the broad potency of an ideology that was commonly taken for granted. Notions of linear developments and actual truths gave way to reconstructions of detours and wrong turns, of parallel philosophical and historical narratives, and power relations.

Pursuant to this rhizome-like understanding of genealogy, in the following I would like to take a look at this catalogue, which presents something of a genesis of Felix Kultau’s work between 2017 and 2021, through the prism of a “genealogy of nostalgia”. If we understand morality as something that has grown historically, this also implies that it could just as well have manifested differently if power relations had been different. If, as a result, it is no longer possible to assume incontestability and objectivity, it seems all the more interesting to reflect – as I would like to assume Kultau does here – on the means by which certain values have become established. In a present overwhelmed by accelerationism, the logic of progress and the desire to (self-)optimise, the awakening of a retrospective longing notably emerges as a powerful political strategy. The nostalgia of the past is blissful and joyful, a “longing for [ . . . ] the time of our childhood, the slower rhythms of our dreams” (Boym 2001, p. xv). As a political, commercial, social and psychological tool, it is used to influence, control, or change human behaviour.Some of the most pressing contemporary problems (ecological crisis, migration and integration, fragmented worldviews, social media, fake news, extremist politics, and terrorism) can be better understood through interactions with individual and collective forces of nostalgia.

Nostalgia’s power lies above all in being a defining, influential human emotion. For Svetlana Boym, one of the most cited and influential critics of nostalgia, it is “the longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed”; it is “a sentiment of loss and displacement, but it is also a romance with one’s own phantasy”; it is “a superimposition of two images – of home and abroad, of past and present, of dream and everyday life.” Nostalgia emerges as the interplay of an idealised image in the imagination of the individual and/or community with “material” topographical features (such as landmarks or buildings), objects and even names. Certain triggers, which Starobinski describes as “memorative signs,” bring to life a whole complex of past or idealised images and experiences that merge different zones of place and time. These “memorative signs” haunt the consciousness with an image of the past, be it true or fictitious, which is now final and indelible.

I would like to argue for understanding Kultau’s sculptures as material as well as emotional collages of these very memorative signs: in the form of stickers, piled up into obelisks, scratched into display surfaces. His sculptures not only draw on a repository of materials and signs, but also on the values of experience and memory associated with them. As a child of Generation Y – the post-MTV generation – Kultau refers to a form of nostalgia that can be read in terms of pop cultural influences. More specifically, it is mostly the American pop culture that began flickering across our screens in the mid/late 1990s and creeping into our consumerism. Stylised as the high culture of globalisation, it promised a kind of universal identification value in an a-political moment. What then became the epitome of individual freedom and democracy now manifests itself – like the home that never existed – primarily as a memory, as pop nostalgia. In keeping with the new spirit of capitalism, the failed promises of the global entertainment industry find their way back into the processes of capitalist accumulation. If worn-out jeans were ever a sign of individual non-conformity and attested to one’s own experiences, today stone-washed jeans declaim nothing more than a trend consciousness that has long since left any individuality behind. Confronted with Kultau’s sculptures, we encounter a similar patina, one of revolutionary gestures, promises of freedom and particularism. By bringing together extremely diverse memorative signs of this pop nostalgia, his sculptures operate precisely at the point where nostalgia has not only become the epidemic of a society that is overtaking itself, but is also a commodified form that has become a means of manipulation. Again and again, his works play with an awareness of their own existence as objects and the associated commodity fetish (as lamp, door, display or suchlike), only to then retreat into their own existence as signs and nostalgic functionlessness. And although we are well aware that it is American pop culture – in other words, pure capitalism – that is speaking to us, Kultau succeeds in evoking a feeling of longing in us that not only reconstructs a consumer nostalgia but also allows us to feel the complexity of a genealogical interlocking of longings, memories and values: individual, collective, true, and fictional.

Hendrike Nagel

list of references

1. Jean Starobinski, The idea of nostalgia, Diogenes 54, 1966

2. Svetlana Boym, The future of nostalgia, Basic Books, 2001