L +

Artworks

Information

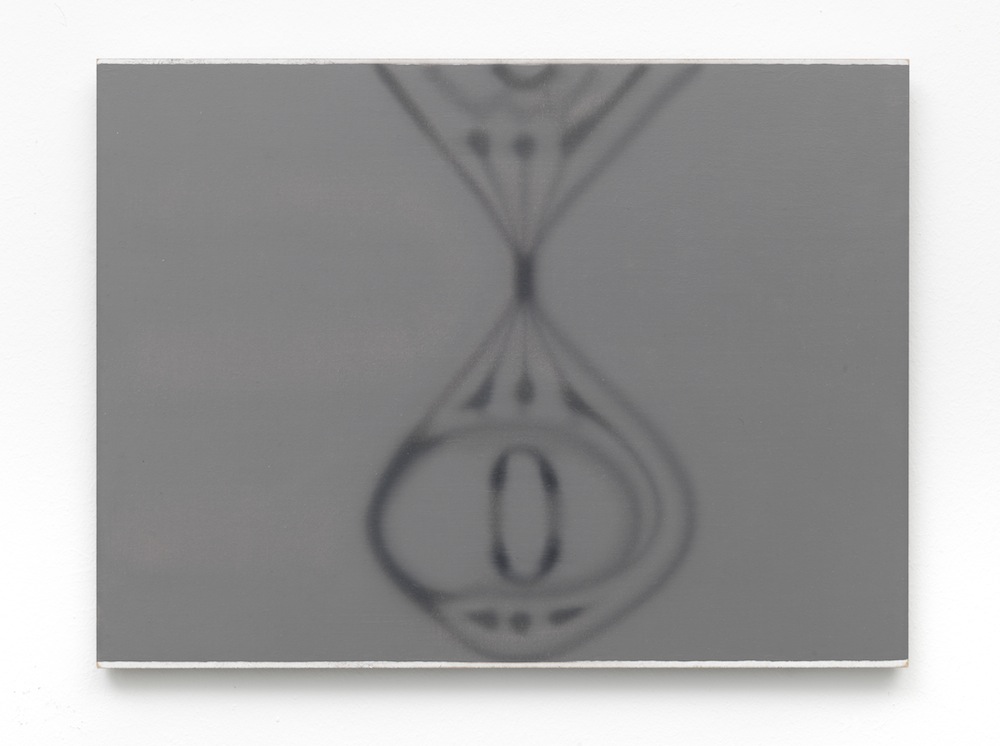

Without warning, the physical world begins to crystallize. Living material mineralizes into a hybrid state that is neither alive nor dead. Seemingly out of nowhere forests across the globe begin to crystallize. The crystallization spreads, enveloping everything in its path, including animals, buildings, even people. This is the alarming process described in J. G. Ballard’s 1966 novel Crystal World. The only experience in real life that might come close to this inexplicable transformation is the ice storm, in which snow or rain freezes on contact, forming a coat of ice on the surfaces it touches. Also referred to as a “glaze storm,” it is caused by freezing rain. The raindrops move into a thin layer of below-freezing air right near the surface of the earth. Ice storms have the bizarre effect of entombing everything in the landscape with a glaze of ice so heavy that it can split trees in half and turn roads into lethal sheets of smooth, thick ice.

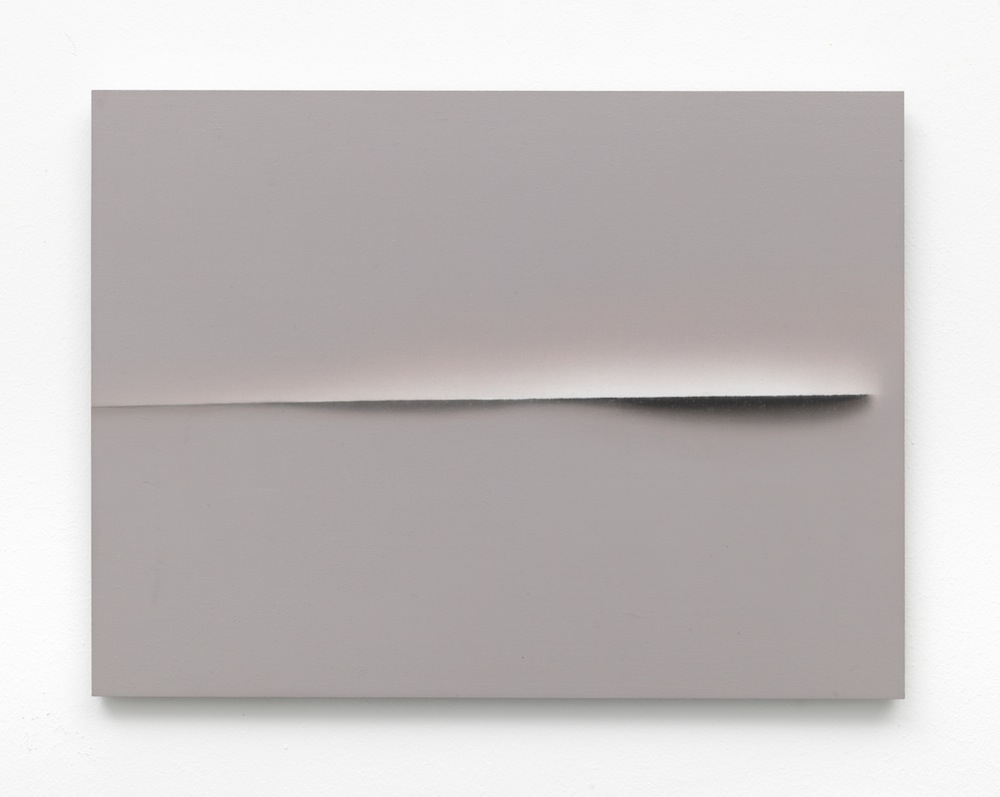

I think of this extreme meteorological phenomenon when trying to come to grips with a 2009 painting by Stehn Raupach, the excellent German painter that many years ago was a student in the class of Christa Näher in the Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. The painting in question was installed just a few meters outside my office for a while, and I looked at it in deeply fascination every time I passed it. On one level it is a totally traditional image depicting a living room with plants, furniture, and a window through which we get a glimpse of the garden. The foliage is so close it almost touches the glass. Think of all the windows modern art has on offer, from Henri Matisse onwards. But this one is different, totally different.

“In the future everything will be made of chrome,” is a statement from an American animated television series that has inspired Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija, who since many years produces silvery objects, tables and chairs, an entire kitchen. In Raupach’s image everything seems covered by a reflective surface, as if transformed into quicksilver. The painting is technically perfect, a bit like the objects Jeff Koons created in the mid 1980s. Think of that legendary silvery rabbit by Koons, it could inhabit Raupach’s living room and feel perfectly at home.

Most of us think of light as a positive force - benevolent, beatific, illuminating - even a symbol of goodness. But it can also be harsh and corrosive. Sometimes light in a painting is so bright that it virtually obliterates the subject matter. This happens in Turner and in some impressionist masterpieces. Modern technology has created even more extreme moments, like the scene in Terminator 2 in which a shock wave of bright light wipes out an entire metropolis, turning it into white dust.

In Raupach’s painting everything is light and reflection. The glare on the floor is so bright that nothing more really is visible. There is only a whole of pure radiance. The rest of the world has been turned into a weird mirror, as if the role of all the things that surround us could be reduced to one single thing: to reflect light. Perhaps for the painter that is what objects are for. Stehn Raupach’s quicksilver painting seems to make that claim. Whoever has spent some time with it will have problems forgetting it and will wonder what the artist has to offer beyond this crystal image. For me, that doesn’t really matter. This picture is enough. It’s a rare example of a contemporary painting that seems to me in every sense of the word perfect.

Daniel Birnbaum